New Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab: what we know so far – and why more research is still needed

For the first time since 2003, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a novel treatment for Alzheimer’s disease in the US – on the condition of further successful trials. The drug, called aducanumab, has the theoretical potential to slow down the cognitive deterioration typical of Alzheimer’s disease.

Plenty of debate has followed the drug’s approval, with many scientists expressing concern over the lack of clinical trial evidence for the drug. Others are concerned because the drug previously failed two clinical trials – and the data from these failed trials was used when advocating for the drug’s approval.

This has left many asking why the drug has been approved in the first place, and on what grounds, as current evidence doesn’t seem to conclusively suggest it can provide improvements for those with Alzheimer’s disease.

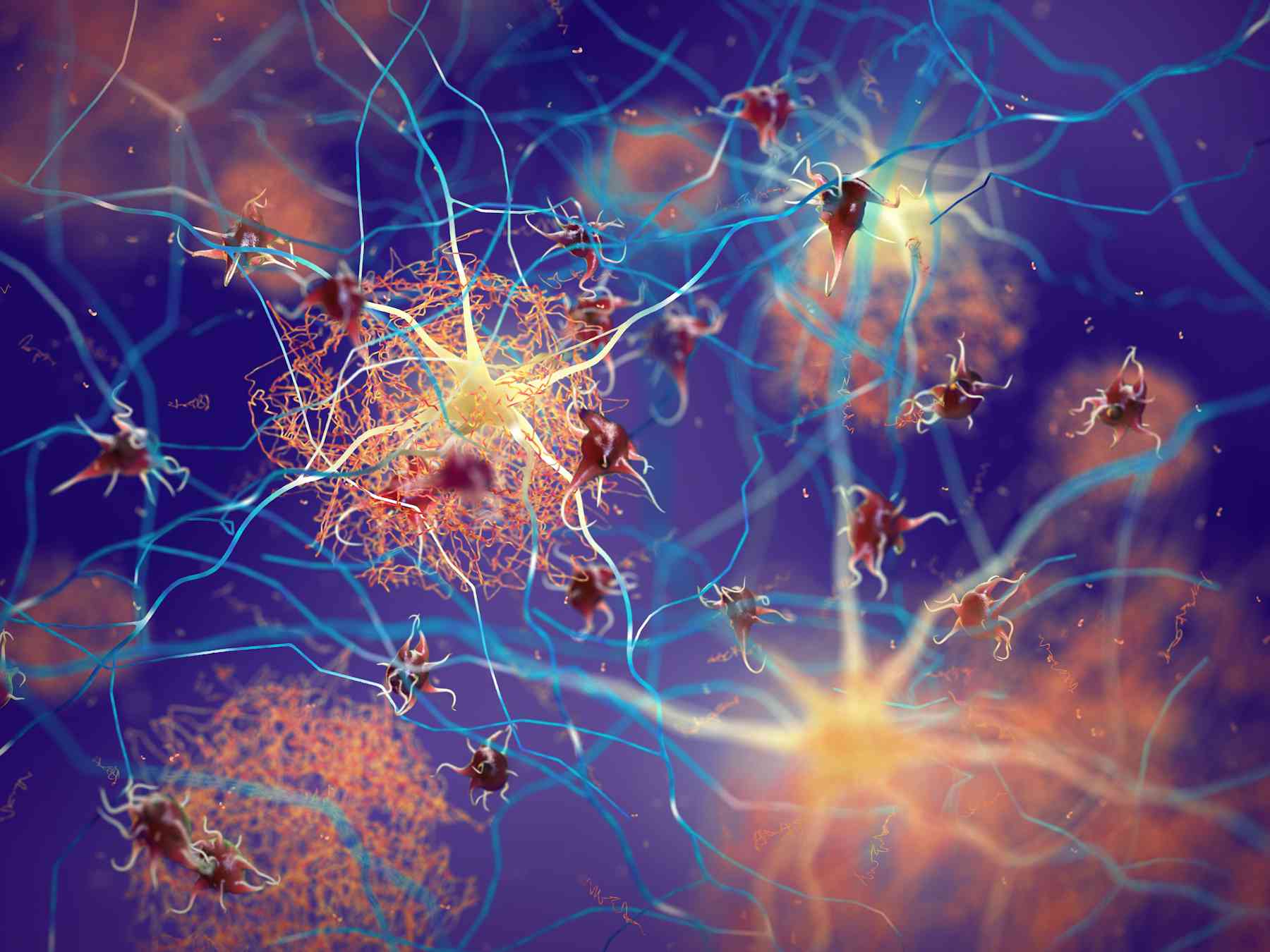

Beta-amyloid plaques

Aducanumab works by targeting beta-amyloid plaques in the brain.

Every person has beta-amyloid in their brain. This peptide plays an important role in many beneficial brain functions, including promoting brain healing, synaptic function (which allows brain neurons to communicate), and even suppressing tumours.

But beta-amyloid can become toxic when it groups together and form plaques in the brain. These plaques disrupt the function of brain cells and their ability to communicate with each other – which may lead to cognitive issues, such as memory loss.

Yet beta-amyloid plaques aren’t the sole cause of Alzheimer’s disease, nor are they the only cause of cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s disease is complex, and can be caused by both genetic and non-genetic risk factors (including certain medications, lifestyle, and even environmental factors, such as air pollution).

Alongside beta-amyloid, other proteins, such as tau, are greatly involved in the disease. Uncontrollable neuroinflammation – which can be caused by many factors, including injury, disease, or stress – is also common in patients with Alzheimer’s and may promote the development of the disease.

Importantly, beta-amyloid plaques have even been found in otherwise healthy people – which contradicts the theory that plaques are the cause of Alzheimer’s, and that getting rid of them will halt the disease altogether. Having said this, given beta-amyloid is involved in many important brain functions relating to Alzheimer’s, targeting it may prove to be beneficial – but more research will be needed that definitively shows this.

Aducanumab

The new drug aducanumab is an antibody. Antibodies are special immune proteins our body makes that bind to specific targets found in pathogens (such as bacteria or viruses), or even in other proteins. For example, in autoimmune diseases, antibodies against our own proteins are produced by our body, which leads to often devastating symptoms. Antibodies that target specific proteins or peptides (parts of a protein) can also be produced in the lab.

In this case, aducanumab works by targeting the beta-amyloid plaques in the brain by binding to them. This signals that there’s a threat to the brain’s immune cells, which then come and remove the plaques. In both human and animal trials, aducanumab has been shown to reduce the amount of plaques in the brain.

But aducanumab’s only target is the plaques, meaning other aspects of Alzheimer’s (such as neuroinflammation, or the death of brain cells) remain unchanged. As such, although a reduction in plaques has been seen, aducanumab hasn’t been shown to slow down cognitive decline – although it was hinted. In the past, previous trials of aducanumab were stopped early because the developers felt they were unlikely to see improvements in cognitive decline or slow it down.

However, after re-examining a subset of the data from these previous trials, Biogen – the company which produces aducanumab – claimed to have found evidence that in some cases high doses of the drug might reduce cognitive decline. This re-examination ultimately led to it receiving FDA approval. The FDA, however, has put as a term of the approval that a further study is conducted where these findings are replicated. The results must also show significant clinical benefit for patients.

So is this truly a positive step in the discovery of Alzheimer’s disease treatments?

While there are some hints that a high dose of the antibody taken over 18 months may possibly reduce cognitive decline in some patients, there’s no way of knowing which patients are likely to benefit over others because of the complexity of the disease. This means that while some may benefit of aducanumab, others will still experience a deterioration in their quality of life and memory despite taking the drug. And the drug may cause severe side effects, including delirium, brain haemorrhages and brain swelling.

Given that the drug costs $56,000 annually per patient, trial and error with this specific drug is not an easy task and can be a huge cost for everyone involved. And, as it’s the first drug approved in over 20 years, it might encourage other pharmaceutical companies to generate their own version of the antibody, while steering away from research focused on finding new pharmaceutical targets.

Most importantly, there is currently no guarantee the drug will slow cognitive decline – which could be devastating for patients in more than one ways.